|

|

| As seen in the | |||||

| January 21, 2002 | |||||

State making its Web sites ADA compliantBy Diane Weaver Dunne |

|||||

|

Connecticut is ahead of the national curve by ensuring its government Web sites are accessible to individuals with disabilities. A state policy adopted two years ago on the 10th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act requires state Web sites be accessible to people with disabilities. A volunteer group of 15 state employees have been forging ahead to guide the redesign effort of more than 158 separate state Web sites to be compliant with guidelines established by the World Wide Web Consortium. The state is developing a new portal with built-in technology to make all state Web sites automatically accessible for those using assistive technology, said Nuala Forde, spokeswoman for the Office of Information Technology. |

|

||||

| "[The Internet] is a

powerful tool for the disabled to access the wealth of information the

Internet provides," Ford said. "It gives the government and

private sector a new way to reach this population who may not have any

other means to access what most people take for granted."

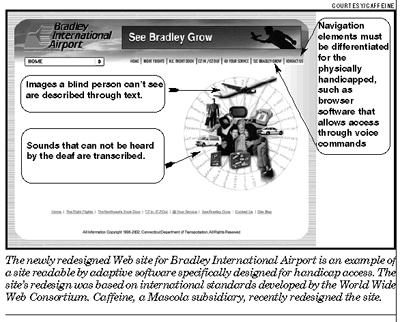

The state's efforts over the past two years have been ahead of a federal law, Section 508 of the Rehabilitative Act Amendment, that went into effect last June requiring all federal agencies make their electronic and information technology available to the disabled. There has been confusion about whether state agencies are subject to Section 508. According to Doug Wakefield, an information technology accessibility specialist with the federal Access Board, Section 508 does not require state agencies or federally-funded agencies to comply. But, there are other federal laws, such as anti-discrimination and education rules that do apply to particular state agencies, Wakefield said. "[Section 508] has 16 basic provisions that need to be followed by federal Web masters so the output of the Web is compatible with assistive technology," Wakefield said. The accessibility initiative cost the state about $10,000 to train about 150 state Web masters. About 35 sites have been certified or are under review for certification, and another 91 are working towards certification, Forde said. The state's movement to make sites accessible is very important to the disabled, said Rebecca Earl, president of the New England Assistive Technology Marketplace. Sites not redesigned expand the digital divide, Earl said. Kathleen Anderson, a Web master for the state comptroller's office, is leading the state's effort. A message she read in a chat room several years ago influenced her to believe advances in Web design were short-changing those with disabilities. The e-mail was from a woman whose husband is blind, and wrote how the Internet had been a great place for her husband during its infancy when most sites were primarily text and software read information back to him. When Web masters turned the Internet into a TV-like thing, his access to the Web diminished, Anderson said. "I said 'that’s not fair.' [The disabled] were there first. Who are we to take this away?" Providing Web site access to those with disabilities was the motivation behind the redesign of Bradley International Airport's Web site. Bradley, a client of Caffeine, an Internet marketing company and a Mascola subsidiary, recently completed the airport's Web site redesign. "If you want to create a visually appealing Web site for the enabled and appealing to the disabled, that's where the real challenge lies," said Bill Mulligan, president of Caffeine. Any individual with a disability can access Bradley’s Web site by using acceptable and available computer hardware, said Dan DeLauro, a Web developer for Caffeine who worked on the project. "An accessible Web site is one that is readable by adaptive software specifically designed for handicap access," DeLaura said. "Such software reads and interprets HTML, and speaks it back (or delivers to a Braille encoder) to the user with disabilities. In order for this to be done successfully, the Web site's mark-up language, or code, must be written in a manner in which it will be correctly conveyed and interpreted." For example, images a blind person can't see must be described through text; sounds that can not be heard by the deaf must be transcribed; and navigation elements must be differentiated for the physically handicapped, DeLaura explained.

|

|||||